How Migration Really Works

As someone who moved from Patna to Noida to Mumbai to Noida to London, who finds the idea of circular migration appealing, and who has long dwelled on the ideas of roots, places and belonging, coming across this eponymous book was fortuitous.

Written by a Professor of Sociology after over 30 years of rigorous research, it shares insights on why everyone from politicians (both on the left and right), media and international organisations, to interest groups and NGOs exaggerate the pros and cons of migration in their own interests.

It also debunks the many myths surrounding the subject.

Our societies are not more diverse today than they were in the past. Such presumptions of homogeneity are based on a distorted and Euro-centric view of what diversity means. Global migration rates have been constant over the last century.

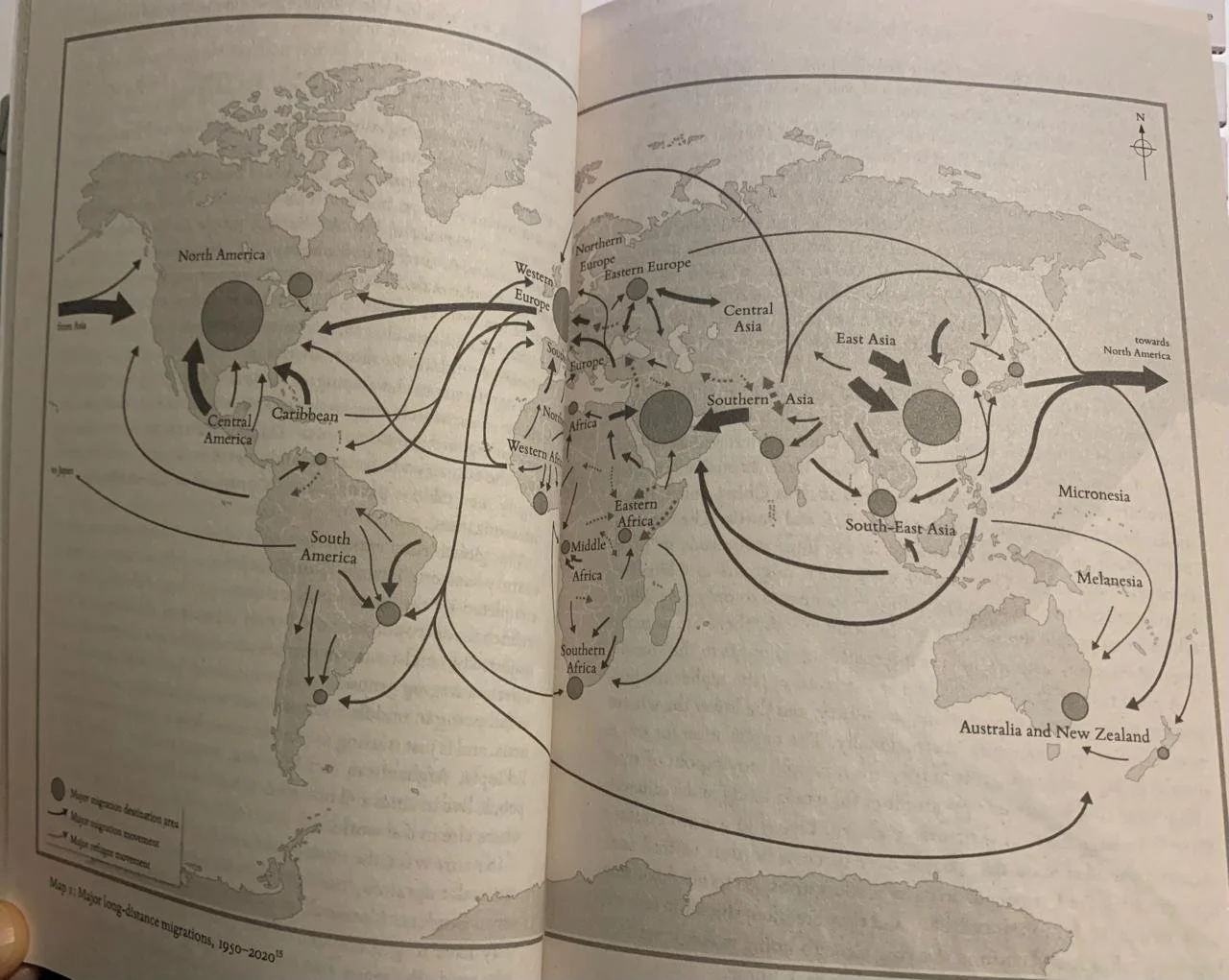

Most migrants don’t leave their homes out of desperation, nor is it a natural, spontaneous phenomenon. It was set in motion by destination cities or countries looking to address labour demand (for work migrants) or fund shortages (in the case of higher educational institutes targeting foreign students). Also, the vast majority moves within countries (internal migration) or to neighbouring areas in search of better opportunities.

The map contradicts the idea of a South-North exodus.

Something we all suspected but perhaps never articulated is that the rise of shopping malls and supermarkets in big cities has led to people living more isolated lives in neighbourhoods (also looking at you quick commerce!). In creating superfluous needs and closing down mom-and-pop stores, we risk losing out on vibrant centres of social exchange that keep communities alive and kicking.

Immigration getting crime rates soaring is a double myth because there is accumulated evidence to support that crime rates have dropped as immigration has increased. Also, the fiscal impact of immigration and its effect on wages or unemployment – whether positive or negative – is negligible.

Government austerity, and not refugees, has caused the social housing crisis in many Western countries. Speaking of housing, segregation is not alarmingly high. Compared to the US, Europe does not have a recent history of official, government-endorsed racial segregation, which makes integration between different ethnic groups relatively easier. Also, the concentration of similar groups in one area is not necessarily a bad thing, if done out of free will and not discrimination or exclusion. It can empower disadvantaged minorities to get access to socioeconomic mobility through solidarity, self-help and entrepreneurship.

There is no left-right divide on immigration – instead, they are divided internally. Left-wing governments try to strike a balance between the interests of labour unions that prefer restrictive policies and liberal and human rights groups that favour more open policies. Similarly, right-wing governments cater to both business lobbies that favour immigration and cultural conservatives that ask for restrictions. Though to be fair to labour unions, they oppose large-scale recruitment of foreign workers because they suspect their employers’ motives (undermining strikes or driving a wedge between native and migrant workers), but once recruited, their natural reflex is to defend the rights of all workers in class solidarity. Even conservatives across religions are taught to protect the vulnerable and asylum seekers.

Contact with immigrants reduces xenophobia. I’ll take this argument further, having lived the experience during my post-graduation – contact with anyone you deem ‘the other’ or are unfamiliar with, also removes subconscious stereotypes you may have about them. As someone who had barely interacted with people outside of North India, living with classmates from different parts of the country as a first-time hosteller was an eye-opener. This is in line with psychology’s ‘contact hypothesis’ that along with many similar social science studies, confirms how actual interactions between minority and majority groups reduce existing prejudices. This is also the reason why hate-mongers target syncretic places of worship first, to dissuade such interactions in pursuit of their political goals.

If you open borders, immigration patterns will have people moving back and forth between countries in free circulation. Restrictive policies, paradoxically, discourage return migration. The EU is a live case study. Contrary to widespread East-West migration fears (post the fall of the Berlin wall), and in light of considerable income differences between the European countries, long-term migration trends remained minimal.

There are many other points that I haven’t covered (on illegal migration, brain drain, remittances, refugee crisis, smuggling, trafficking, climate change, and dignity of labour) which deserve a comprehensive read.

This book does not try to soft-pedal real, on-the-ground challenges but lends a holistic view of cause and effect. It urges readers to question empty or misguided rhetoric and think hard about the kind of societies they want to build.